Author: Marie Ekström

How does one assess and mitigate a risk that is constantly evolving and conditioned on future human actions? This is the challenge insurers face as they plan for a future shaped by today's decisions. In this interview, Gallagher Re's Dr. Marie Ekström, and Dr. Marina Baldissera Pacchetti of University College London (UCL) address questions around climate risk management in (re)insurance. They cover key technical and philosophical issues in building resilience towards climate risk.

1. How does the extended timeframe of climate change impacts create unique challenges for financial risk management, particularly within the reinsurance sector?

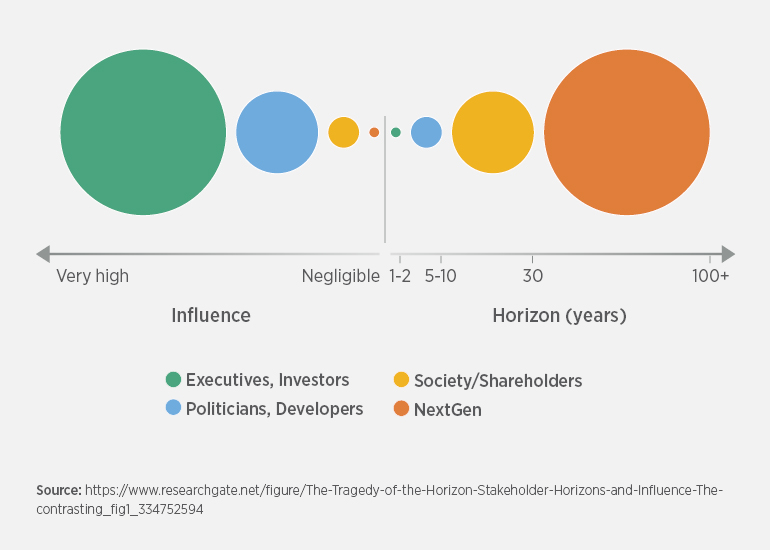

A major challenge in managing climate risk is the mismatch between policy and impact horizons. In 2015, Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability board, coined the phrase 'Tragedy of the horizon', referring to the idea that long-term climate risks are borne by future generations, while today's policies remain short-sighted.

When the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) surveyed the industry, many respondents flagged the difficulty of working toward far-future climate horizons. If the typical business planning horizon is 3-5 years, how can firms design meaningful objectives for risks that manifest over decades?

Tragedy of the Horizon: Stakeholders and Influence

Source: The role of traditional discounted cash flows in the tragedy of the horizon: another inconvenient truth, Global Change Journal.

2. Catastrophe models are relied upon to link information about hazard, exposure, and vulnerability to financial loss. To what extent are these tools also applicable to forward-looking risk management?

It is important to remember that catastrophe models are designed for pricing current risk. Hence, model structures are informed by observed relationships between the three risk components (hazard, exposure and vulnerability) and financial losses.

Consider a shifting time horizon. Over time, if hazards are responding to climate change, it is reasonable to assume that societies will adapt to a changing risk landscape; people build flood defenses, revise building codes, or relocate. Hence, with time, expect change in all three components of the catastrophe model and their relationship with losses. In addition, whilst in a current setting, catastrophe models reflect one specified observed climate reality. A forward-looking application has to consider multiple plausible futures associated with different climate risk.

Nevertheless, in lieu of approaches that provide comprehensive predictive information about future losses, catastrophe models can be applied to give a conditioned view of how losses may change. Typically, only the hazard component is adjusted to be representative of a particular climate scenario, other components of the model are assumed stationary.

"Models calibrated to current reality will eventually become uninformative as society adapts to a changing risk landscape. The industry may require alternative, less constrained approached to explore plausible financial losses due to catastrophic weather-driven events.”

- Dr. Marie Ekström

3. How does interdisciplinary research, such as that conducted in large-scale EU projects, contribute to developing more effective climate risk management strategies for the reinsurance industry?

Interdisciplinary research helps combine climate science with social science, economics, and sector-specific expertise, ensuring climate risk information is usable in addition to reflecting state-of-the-art understanding of climate-related hazards.

Projects such as Climateurope21 work to support the standardization of climate services so that insurers and other sectors receive high-quality, comparable data. The ASPECT project2 supports the uptake of predictions and projections at different timescales. By drawing on physical and social sciences, these efforts support better-informed decisions across industries.

4. How can reinsurance professionals effectively communicate the complexities and uncertainties of climate change risks to their clients, and what role does transparency play in this process?

Transparency is critical when communicating climate risk information. Because of the many different models, scenarios, and statistical methods involved in the production of climate change information, it is possible to frame very different messages of climate change. Recipients need reassurance that good practice has been followed to avoid misleading guidance.

Key elements of good practice in the context of climate change communication include:

- Using models appropriate to the peril of interest. For example, do not rely on coarse resolution global models for local flood predictions

- Avoid reducing the uncertainty space. Models simulating the current climate can be evaluated against the observed climate, but predictions of the far future are intrinsically unverifiable. Hence, it is important to consider results from a broad range of models that may have different skills in simulating future change

5. Beyond meeting regulatory demands, what innovative strategies can the reinsurance sector adopt to proactively build long-term resilience to climate change impacts?

The expectation to address climate risk is a relatively new and rapidly evolving practice for the reinsurance sector. While it can be difficult to point to best practices, inspiration can be borrowed from sectors further ahead.

Environmental and water management organization, for example, offer valuable lessons. Wilby and Vaughan (2011) identified traits of climate-adaptive organizations that reinsurers can emulate:

- Climate change champions are clearly visible, setting goals, advocating and resourcing initiatives on climate change adaptation.

- Climate change adaptation objectives are clearly stated in corporate strategies and regularly reviewed as part of a broader strategic framework.

- Comprehensive risk and vulnerability assessments are being undertaken for priority activities at early stages of the business planning cycle.

- Scientifically based, workable guidance and training on adaptation is being put in place for operational staff.

- Flexible structures and processes are in place to assist organisational learning, up-skilling of teams and mainstreaming of adaptation within codes of practice.

- Adaptation pathways are being guided by the precautionary principle in order to deliver 'low-regret' anticipatory solutions that are robust to uncertainty about future risks including, but not exclusively, climate change.

- Multipartner networks are in place that are sharing information, pooling resources and taking concerted action to realise complementary adaptation goals.

- Progress in adapting is monitored and reported against clearly defined targets.

- Effective communication with internal and external audiences is raising awareness of climate risks and opportunities, realising behavioural changes and demonstrating adaptation in action.