Effects across Asia Pacific

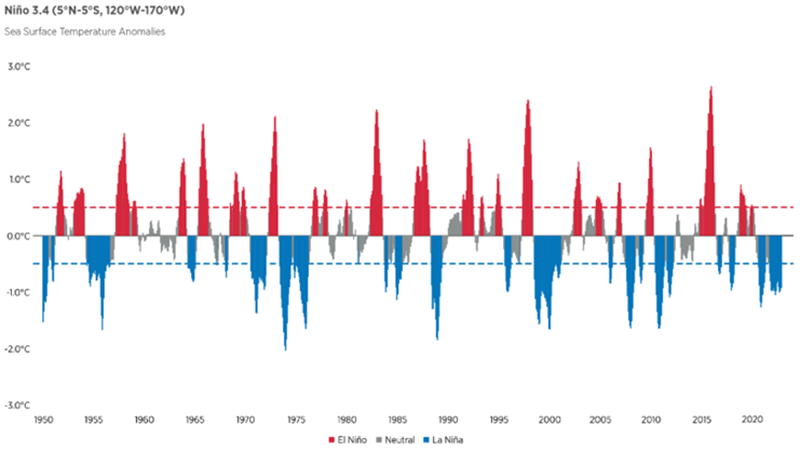

The maps below highlight observed weather patterns globally during El Niño and La Niña phases. Outcomes vary, depending on the intensity of the phase, the time of year it develops and the interaction with other climate patterns.

Broadly speaking, for Asia Pacific, La Niña is often associated with wet conditions in eastern Australia, and with heavy rainfall in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand.

El Niño meanwhile, is often associated with warm and dry conditions in southern and eastern inland areas of Australia, as well as Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and central Pacific islands such as Fiji, Tonga and Papua New Guinea. During the northern hemisphere summer season, the Indian monsoon rainfall generally tends to be less than normal during El Niño phases.

Figure 5. Maps show how ENSO commonly affects Northern Hemisphere winter and summer climate patterns around the globe. Source: NOAA

Details regarding regional and country specific rainfall relationships with ENSO phases are detailed briefly in the following table and in more detail in the text. Because the interplay between the various climatic patterns is complex, it's important to identify their various phases to understand any offsetting effects.

| West North Pacific basin |

Tropical cyclones (TCs) form more south-easterly |

TCs form more north-westerly |

Positive: North Asia affected by TCs |

| Australia |

Reduced rainfall, possible droughts leading to increased risk of bushfires |

Increased rainfall, possibility of flood events |

Positive: Reduced rainfall, increase risk of bushfires

Negative: Increased rainfall |

| India |

Reduced rainfall during monsoon season |

Above-average rainfall during summer monsoon |

Positive: Increased rainfall

Negative: Reduced rainfall |

| China |

Increased rainfall in southern China and reduced in northern China |

Reduced rainfall in southern China and increased in northern China |

Asymmetric influence |

| Japan |

Increased rainfall in western Japan during summer |

Increased rainfall in Southwest Islands during summer |

|

| Southeast Asia (Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore) |

Reduced rainfall |

Increased rainfall |

Positive: Reduced rainfall in Indonesia. Increased rainfall in Vietnam

Negative: Increased rainfall in Indonesia |

| South Korea |

Increased rainfall |

Reduced rainfall |

|

Western North Pacific Typhoon

- In the Western North Pacific, El Niño phases correlate with higher typhoon frequencies across much of the basin. In general, the ENSO correlation with landfalling typhoon frequency in the Northwest Pacific is less than with Atlantic landfalling hurricanes, however storm formation often occurs more frequently in the seas east of Guam during El Niño phases, with increased incidence of recurved tracks towards the part of the basin closest to Japan.

- El Niño conditions favor longer-lived and more intense storms, compared with La Niña conditions.

- The IOD is currently in a positive phase, which is expected to last during the rest of the WNP Basin Typhoon season. Historically, a positive IOD has tended to lead to a recurving north-eastward track or a westward path south of 15°N, leading to more tropical cyclones (TCs) impacting Japan, South Korea or South Vietnam.

Australia

- During La Niña events, rainfall north of Australia enhances and typically increases the chance of above-average rainfall for eastern, central and northern parts of Australia. Insured losses are typically higher for La Niña than El Niño in Australia.

- During El Niño, the opposite is true. Rainfall is usually reduced through winter-spring in Australia, especially across eastern and northern areas.

- Whether Australia experiences strong drought or fire weather conditions during El Nino is dependent upon two other drivers: the IOD and the Southern Annular Mode. These drivers are sometimes more important than ENSO: 2019-2020 was ENSO-neutral, yet Australia had record-breaking extreme fire weather and months of major fire events largely due to the other drivers.

India

- ENSO impacts the arrival and strength of the Indian southwest monsoon, in part due to modification of the Walker Circulation – a Pacific-wide zonal circulation in tropical latitudes that affects convection over the equatorial Indian Ocean and consequently, rainfall over continental India. El Niño generally suppresses the southwest summer monsoon rainfall in India whereas it's often enhanced by La Niña. As a result, previous El Niño conditions have often coincided with droughts (e.g., 2002), whilst La Niña conditions have often coincided with above-average southwest monsoon rainfall, enhancing the potential for flood events.

- A Gallagher Re investigation of available data indicates there is increased probability of hail occurrence in northeast India during the positive phase of ENSO. In northeast India, 86% of hail events between 1981 and 2015 occurred during periods with a positive ENSO index.

- A positive IOD creates a conducive environment for tropical cyclones to form in the Indian Ocean.

China

- Southern and East-Central China. Positive correlation between ENSO phase and autumn/winter rainfall in southern China. This positive correlation typically migrates eastward during the mature ENSO phase (often in winter) into southeastern China and then into eastern-central China during the spring. El Niño events often coincide with above-average autumn/winter rainfall in southern and southeastern China and above-average spring rainfall in eastern-central China.

- Northern China. Negative correlation between ENSO phase and rainfall in northern China during the summer and autumn of the ENSO onset year. i.e., El Niño events often coincide with below-average rainfall in northern China during the early stages of the El Niño phase with limited correlation during El Niño decay.

- Hong Kong. Generally wetter winters (December through February) and springs (March through May) during El Niño phase make it unlikely to have TCs affecting Hong Kong before June.

Rest of Asia Pacific

- For Japan, El Niño effect leads to greater rainfall in the summer concentrated in western Japan, while increased rainfall in Southwest Islands during summer. The JMA predicts average to high rainfall in both western and eastern Japan this year between July and September. Generally cooler summer during El Niño and hotter summers during La Niña are observed.

- For Southeast Asia, El Niño events tend to reduce overall rainfall, while La Niña years see increased rainfall in most regions. A positive IOD is associated with depressed rainfall.

- For South Korea, El Niño leads to increase rainfall mainly in the southern region of the Korean Peninsula.

Managing the risks of climate variability

As outlined in the paper, the switch from La Niña to El Niño brings a pivot in terms of physical loss, since it correlates to warmer surface conditions. El Niño is associated with higher intensity of temperature extremes, shift in rainfall patterns and general reduction in rainfall across the wider region. And, as explained above, El Niño years tend to be lower for insured losses, compared with Neutral and La Niña years.

Whilst climate change is leading to variability in climate conditions and natural catastrophe events, this impact isn't pronounced in the next year or in the immediate future, butover the longer term.

In a changing world, being equipped with functional risk solutions to assess and quantify catastrophe risk is paramount. Gallagher Re’s team of catastrophe and climate specialists have best-in-class insight and understanding of the current and coming impacts of climate variability on the (re)insurance industry.

Working closely with the Gallagher Research Centre, our experts deploy the latest analytical expertise to identify and assess risk exposures in helping (re)insurers to manage them. With our presence across the Asia Pacific region, we harness our first-hand global and local knowledge, whilst leveraging our academic partners, to help clients navigate through weather and climate uncertainty.