Soon after Hurricane Katrina passed, New Orleans' flood protection system began to give way. Over the subsequent hours, the levees would catastrophically fail in nearly 50 different places, letting in 250 billion gallons of water and submerging entire neighborhoods up to 15 feet.

This unprecedented flooding highlighted what caused Hurricane Katrina to be so disastrous: the complex interplay of natural forces and human infrastructure vulnerabilities.

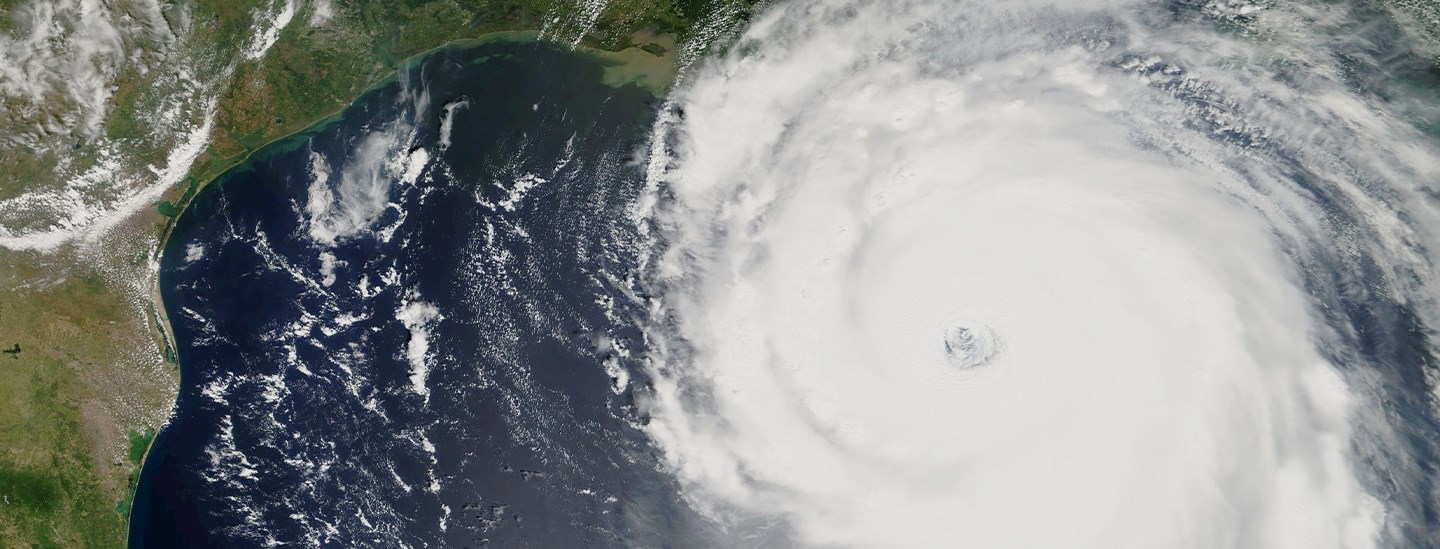

Wind and water: How the events of Hurricane Katrina unfolded

Flanked by Lake Pontchartrain to the north and the Mississippi River to the south, and surrounded by swamplands, New Orleans — famous for its culture and festivals — is situated on a natural basin that, after centuries of human expansion, now lies 6 feet below sea level. The city has long relied on levees and pumps to hold back water, an artificial barrier keeping the "bowl" from filling.

Premonitions of Katrina were observed during Hurricane Georges in 1998, when the waters of Lake Pontchartrain rose to within a foot of overtopping the levees. Engineers sounded the alarm, but meaningful upgrades to the city's flood defenses stalled.

Beyond structural weaknesses, therefore, the devastation that followed also exposed years of delayed actions and overlooked risks.

In the days following Hurricane Katrina, rooftop rescues, emptied store aisles and growing public unrest laid bare the systemic vulnerabilities of emergency preparedness.

The human cost was profound: more than 1,300 lives lost, over 1 million people displaced and over 70% of homes with significant damage.

The economic cost of Katrina in 2005 was USD125 billion, or USD208 billion after being adjusted to today's dollars, according to Gallagher Re. Of that original USD125 billion cost, insurers covered USD65 billion of the total, or USD108 billion in today's dollars, placing it as the costliest natural catastrophe event ever recorded for the insurance industry.1

The aftermath continues to shape the city of New Orleans, with its population remaining at least 26% below pre-Katrina levels2 — a quiet measure of the long shadow the disaster still casts two decades later.

“

Many people [in New Orleans] believe that we didn't experience a climate disaster, but rather a man-made disaster [with Katrina].

Greg Nichols, New Orleans' deputy chief resilience officer

"Many people [in New Orleans] believe that we didn't experience a climate disaster, but rather a man-made disaster [with Katrina]", says Greg Nichols, New Orleans' deputy chief resilience officer. The story of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) exemplifies this belief. A deep-draft channel built to create a shortcut between the sea and New Orleans's inner harbor, MRGO amplified the storm surge during Katrina. It funneled in seawater that overwhelmed the city's defenses and left 80% of New Orleans submerged for over a month.

A storm's toll: The ripple effects of Hurricane Katrina

Katrina triggered the largest climate-related mass migration in US history since the 1930s Dust Bowl, displacing more than 1.5 million people across Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. Its economic impact was far reaching, reducing national gross domestic product (GDP) growth in Q3 2005 and disrupting nearly 20% of US oil production, driving gas prices to USD3.05 per gallon (USD5.07 today). The storm underscored the sweeping financial and societal repercussions of extreme climate risk events.

In the days following the catastrophe, it was clear there would also be insurance claims disputes, with some carriers arguing that damage caused by "water" versus "wind" may not be covered under homeowner policies. This sparked considerable controversy and political intervention and changed the approach to property catastrophe insurance.

Wetter storms: The macro trends driving storm damage

Hurricane Katrina wasn't a one-off event; it was a sign of things to come. The past four decades have seen increasing impacts from Atlantic hurricanes.

Human-driven climate change is a key driver of more intense storms, which, combined with urban expansion and related land-use changes, are further increasing exposure, according to Steve Bowen, chief science officer at Gallagher Re.

"Improvements in attribution science give us more insight into determining the role of climate change on the behavior or intensity of individual events," he says.

"These climate change fingerprints are notably seen with tropical cyclones as storms are growing more intense and bringing severe storm impacts well away from the initial point of landfall. This increasingly means 'wetter' storms are bringing non-wind impacts further inland where communities are not prepared," continues Bowen. "An unfortunate recent example was in 2024 when Hurricane Helene left a swath of considerable flood damage in the Carolinas and Tennessee."

Various National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) branches — such as the National Weather Service and the Weather Prediction Center — have begun integrating hurricane watches and warnings further inland, beyond traditional coastal boundaries.

Like Helene, Hurricane Harvey in 2017 was an extremely damaging storm. The Category 4 hurricane was a large storm that stalled for several days, unleashing record-breaking rainfall across Texas and leading to widespread flooding across Houston. From an economic standpoint, Hurricane Harvey caused USD125 billion in nominal damage, or USD164 billion in today's dollars. The nominal insured loss was USD35 billion, or USD39 billion in today's dollars.1

"Natural hazards only become catastrophes due to human decisions and actions, or sometimes, inactions," highlights Lorcán Hall, senior advisor to SDG Academy, part of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

For example, in today's urbanizing world, communities have more exposure to natural perils, even before accounting for the added pressures of global warming.

Many sea-level cities are "sinking," with Indonesia's capital, Jakarta, famously subsiding by up to 15 cm a year. At the same time, coastal areas remain densely populated and full of lucrative real estate in many parts of the world.3

These patterns of development and settlement amplify the impact of natural hazards, prompting a shift in how such events are described. Rather than calling events like Katrina "natural" disasters, the UN calls them climate risk events: crises amplified by human development choices.

"While climate change is often a focus of discussion, it can be somewhat distracting," says Hall. "We know that human-induced climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events. However, it is crucial to recognize that we have the power to make different and better decisions regarding our responses."

This shift in terminology from "natural disaster" to "climate risk event" is more than a semantic change. In an era of compounding risks, reconsidering calamities like Katrina as natural and human-made disasters is essential for rethinking resilience, preparedness and sustainable development.

CONNECT WITH US

Published August 2025