Author: James Reda

A well-thought-out compensation philosophy is an integral part of any company's talent management program. In the ever-changing landscape of total rewards, organizations are challenged to build competitive and sustainable pay programs that help recruit and motivate key talent while supporting strategic objectives. Employers of choice need leaders who will not only drive profitability with their personal performance, but will engage the organization's workforce as a whole.

Key talent includes executives, critical employees that are hard to replace and/or high potential employees, who are the leaders of the future. The cost of losing key talent is substantial. In addition to the real costs of recruiting and training key talent, there is an unknown but very real opportunity cost of not having the right key talent in the right place at the right time.

Deviation from a compelling and market competitive compensation philosophy may negatively affect a company's ability to attract, retain, motivate and develop key talent. Too often, boards of directors and other compensation decision makers discover their compensation philosophy and subsequent offering is inadequate when it's too late: a key player is lost to another organization or industry, or the company is unable secure a top recruit because their value proposition isn't persuasive.

A compensation philosophy must be approached strategically and comprehensively – it cannot be an afterthought. Companies in different industries and at different stages of development may have differing compensation philosophies. As a result, it's very important that companies understand the compensation philosophy "norm" among both direct competitors and the general industry in order to ensure that their own plans and programs are sufficiently competitive in terms or structure and value.

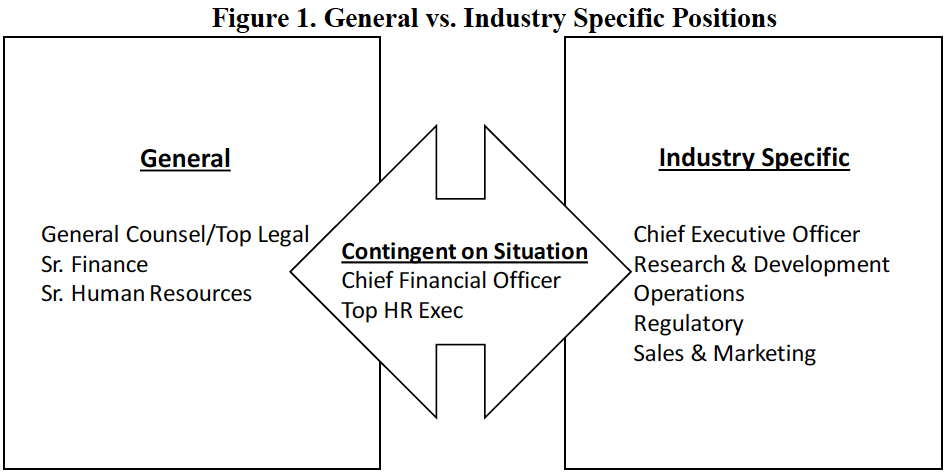

Today, the talent pool is becoming more homogeneous. Key talent are moving between organizations without regard to size (small or large) and type (public or privately held). Some key executive positions are even able to move fluidly between industries, adding another layer to the raging war for talent. While a CEO generally requires business-specific expertise and is likely confined to a career in one industry, other positions – particularly senior legal, finance, or human resources managers – may be able to "industry hop" once or twice. Companies need to pay attention to these trends, which can directly affect their ability to attract key executives. See Figure 1 for a summary of positions that are more "General" (able to move industries without much difficulty) and "Industry Specific" (generally limited to a single industry).

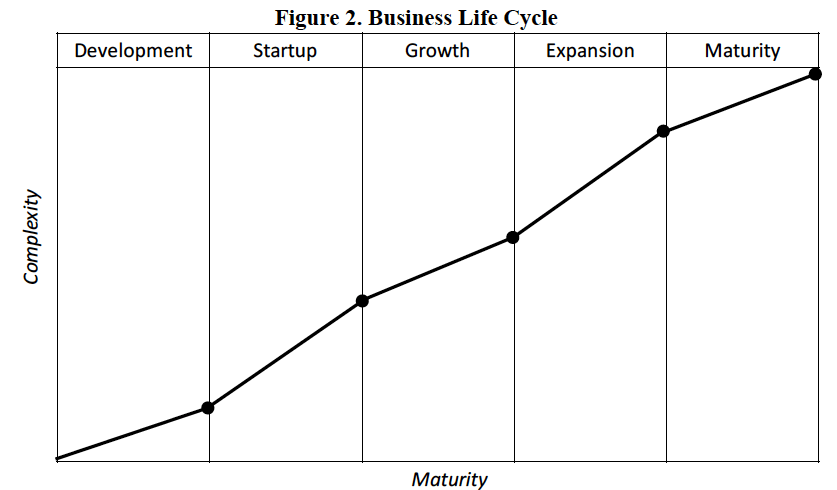

Some companies in early stages or high growth industries (e.g. high technology) try to conserve cash by offering nominal salary and annual incentive levels combined with significant equity awards. This strategy can be an effective form of talent management for companies with high corporate performance, as equity awards are sizable enough to make up for the low cash compensation. However, if corporate performance is substandard (e.g. the stock price underperforms), key executives are left with low relative salaries with no incentive payout or accumulation. This results in significantly reduced executive retention and motivation, with executives searching for more stable, cash-rich compensation plans and/or a better performing corporate environment. On the other side of the spectrum, a mature company that offers a high base salary opportunity may tend to offer lower risk incentive opportunities – the dramatic compensation growth that might be possible with a high performing startup or growth company is not often seen at an expanding or established company.

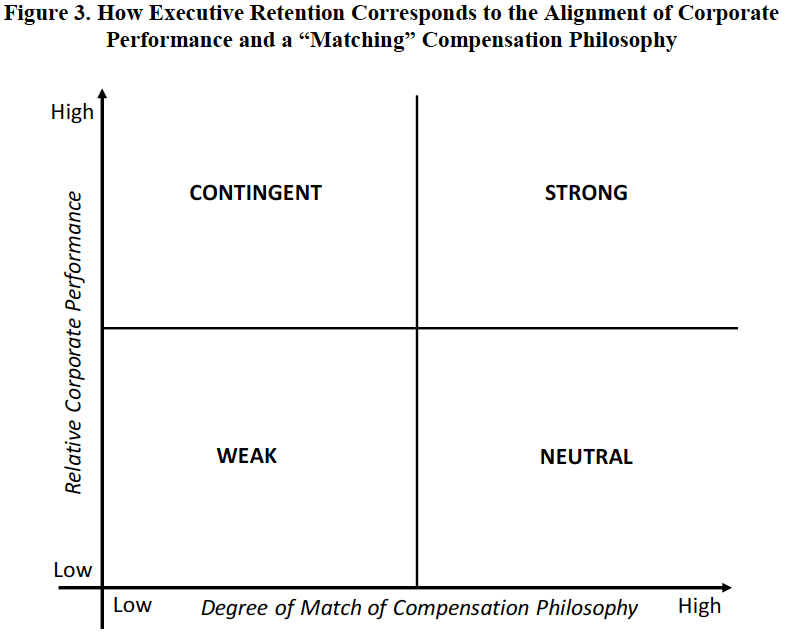

In order to maintain and improve executive retention, it is imperative that companies' understand how their compensation philosophy stacks up or "matches" both specific industry competitors and the general industry. Faltering corporate performance (relative to competitors and/or the general market) combined with a compensation philosophy that deviates from the norm results in weak retention. A CEO at this type of company may look to join a competitor; a more fluid position like a General Counsel may jump ship to a different industry altogether. On the other hand, robust corporate performance combined with a compensation philosophy that is aligned with the market creates a strong executive retention platform. It is difficult for an executive to feel disengaged from a company that appropriately awards high performance. High corporate performance combined with a deviating compensation philosophy (e.g. low cash and high equity potential) can go both ways, leaving some executives in search of more stable compensation in case performance deteriorates, and others motivated and encouraged by similar or even better performance in the future.

See Figure 3 for a summary of how relative corporate performance and the extent to which the compensation philosophy "matches" industry-specific competitors and the general industry will affect retention and recruitment efforts.

Due to a variety of reasons, including new accounting rules, response to investor concerns and a desire to strengthen the link between pay and performance, many companies are shifting their emphasis in executive long-term incentive programs from stock options to performance shares. A major cause for this shift to performance shares is driven by the desire to use a variety of performance measures rather than simply using stock price as the only measure to better align financial performance with incentive payouts.

The latest rules for accounting for stock awards (FASB ASC Topic 718 which replaced FAS 123R in September 2009) have dramatically improved the accounting for performance shares in relation to stock options. In fact, the new rules even allow for a discount to be applied to performance shares that are based on market price conditions. Further, many companies are exploring performance shares that vest based on non-stock price measures because the expense can be reversed for nonperformance (unlike stock options, time-based restricted stock, and performance shares with stock price related performance measures).

Evaluating and communicating executive compensation programs has never been more critical. The unique environment of the company and the individual needs of executives must be considered as compensation programs are designed. In addition to these considerations, public scrutiny of executive pay decisions and practices and the ever evolving governance environment complicates the overall process of setting executive pay.

To help navigate through the maze of competition for key talent as well as new rules and investor concerns, we recommend that the company's compensation philosophy be reviewed and in some cases recreated from scratch.

Simply put, a compensation philosophy consists of the following five components:

- Compensation program objectives.

- Internal vs. external pay equity.

- Company culture fit

- Peer group comparisons.

- Compensation

- Performance

- Pay positioning strategy.

- Percentile ranking of components of pay vs. market

- Pay mix

- Pay for performance curve

- Performance alignment with business plan.

Compensation Program Objectives

A compensation philosophy is not a pay policy that lays out the specific details of a company's plans and programs. Rather, most stated compensation philosophies are really compensation program objectives or guiding principles that drive how a company will approach compensation.

The compensation program objectives are at the core of the compensation philosophy, and set the stage for the other four components. In a way, the compensation program objectives serve as an overall mission statement for your plans.

In general, most companies cite similar items in their compensation program objectives, such as:

- Source of market data: Peer group data is obtained for all companies whether it be from proxy statements and/or private databases.

- Pay positioning: Most companies target the median for all pay components, with adjustments for a variety of factors such as experience, tenure, performance, future potential, and unique skill set.

- Pay for performance: Almost all companies state that their goal is to tie pay to performance (company/business unit and individual).

- Internal equity: The DNA or culture of the organization. This determines the importance of intrinsic motivation vs. external motivation.

Below are some examples of compensation program objectives from well-managed and financially successful companies:

- "…to align each executive's compensation with short-term and long-term performance and to provide the compensation and incentives needed to attract, motivate and retain key executives who are crucial to long-term success."

- "First, our compensation program is designed to attract and retain the highest caliber employees by providing above industry-average compensation assuming stock price performance. Second, our compensation program provides strong long-term incentives to align our employees' interests with our shareholders' interests. Third, our compensation program emphasizes performance and potential to contribute to our long-term success as a basis for compensation increases, as opposed to rewarding solely for length of service. Finally, our compensation program reinforces and reflects our core values, including customer obsession, innovation, bias for action, acting like owners and thinking long term, a high hiring bar, and frugality."

- "Our executive compensation program is designed with the flexibility to be competitive and motivational within the various marketplaces in which we compete for executive talent, while being subject to centralized design, approval, and control."

- "…to reward our leadership team for delivering results and building sustainable shareholder value." "…align the interests of our shareholders and senior executives by tying pay outcomes to performance over the short, medium, and long term." "…to discourage imprudent risk taking"

An effective compensation philosophy draws upon competitive market and financial data, but will also serve as an anchor for "cultural fit" of the organization and key talent, which is based on attitudes, opinions and levels of commitment, engagement and satisfaction. Up until now, most research has deemed cultural fit as independent and from other parts of the compensation philosophy. However, ground-breaking research shows that compensation alignment is a gateway leading to cultural fit and overall employee satisfaction.

The current mindset is that key talent are more closely aligned with intrinsic rewards than extrinsic rewards. In other words, motivation is more dependent on culture fit and level of employee engagement versus what other companies are doing. A successful employee must have positive feelings towards their company and position in order to effectively lead and innovate. It is widely accepted among organizational researchers that factors such as relationships with supervisors, teamwork, career growth, and belief in the products/services offered by the organization tend to explain the bulk of engagement within a typical workforce. But what about compensation?

The interrelationship between the heart or cultural DNA of an organization and an effective compensation philosophy is interesting. Historically, compensation-related items have rarely manifested as top drivers of engagement, as many organizational researchers have heavily discounted the impact of compensation as an efficient pathway to building a highly engaged workforce.

However, our firm's recent research clearly shows that compensation can be a powerful mechanism for shaping a culture of excellence. Recently, we have undertaken a series of studies that reconsiders the relationship between compensation and engagement—and our preliminary findings strongly suggest that compensation is far more important than has previously been noted. These emerging findings show that when employees view compensation more favorably, their propensity to also feel more favorably toward the key drivers of engagement (relationships with supervisors, teamwork, career growth, etc.,) escalates—which optimizes the likelihood for high levels of engagement to be present. Conversely, when employees believe their pay is not fair, the chances for them to feel favorably toward the key drivers of engagement are significantly dampened—creating an obstacle to achieving an optimally engaged workforce.

To be clear, this emerging research does not mean that typical drivers of engagement we so commonly see (e.g., relationships with supervisors, teamwork, career growth, etc.,) are no longer the most important pathways to building engagement. In fact, they still are. However, it does thrust compensation into a profoundly important position, demonstrating the critical need to develop or maintain a compensation philosophy that will in turn foster employee commitment.

Though not as impactful for key talent, external equity is still relevant. The reliance on market (i.e. what other companies are paying) is a function of many factors and is a reflection of the corporate culture. For example, a high-performing company that promotes from within can pay below market levels because the opportunity for job advancement is greater and the expected returns from incentive plans, especially equity awards, is higher.

Also, the confidence in the selected peer group and/or survey data is another factor in determining how much to rely on market data. In general, a company should not rely primarily on peer group comparisons in setting pay. At best, base salary levels should be compared against a broad-based peer group, but should only be used as a general guide for short- and long-term incentive opportunity amounts.

Peer group comparisons have been criticized by almost every pension fund, watchdog group and every special report on executive compensation such as those published by the Conference Board and the National Association of Corporate Directors. However, what other benchmark data do companies really have? How do you properly pay executives?

Top management is less likely to move on to another job as they have invested their career with the company. For them, internal equity is very important. The relationship between pay and performance may have to be adjusted. For example, median payout should follow 60th percentile of performance. This will anchor the long-term plan in median payout for higher than median performance.

Constructing a Peer Group

Of the five components that make up a compensation philosophy, peer group composition is often the most scrutinized and also the most difficult to establish properly.

Peer groups are used basically for two purposes. First, they are used to set the base salary, annual bonus, long-term incentive and other compensation and benefits such as health & welfare plans and other compensation and benefit plans ("Compensation Peer Group"). Second, they may be used to measure the company's financial success compared against the peer group ("Performance Peer Group").

The first step in determining competitive compensation levels is to carefully select a Compensation Peer group. This peer group should consist of at least 15 companies, and usually no more than 20 companies.

The considerations for the selection of the Compensation Peer Group are as follows (in order of importance):

- Direct competitor companies. Companies that you compete with directly in the marketplace for your product.

- Same industry companies with comparable revenues. There are many cases where companies do not compete directly but are in the same industry segment. Care should be taken to select companies with similar profit and growth opportunities.

- Companies ranked by stellar corporate performance, or shareholder return. This practice has been deemed somewhat controversial, as it is less likely that executives can jump industries.

- Companies that you gained executives from or lost executives to in the past 18 months.

- Companies in the same business sector.

- Companies in the same local business area.

While some of these same principles are used to construct a Performance Peer Group, the industry selection is the most important criteria. Company size and the other factors are not as important. Also, the Performance Peer Group tends to include more companies than the Compensation Peer Group.

Compensation and Performance Peer Group development can be a particularly challenging process for companies with:

- Competitors that are based outside the U.S. and/or are privately held;

- Have a unique mix of industry segments; and

- Are significantly below or above industry competitors in size (by revenue, assets, etc.).

The selection of the peer groups is extremely important to a compensation philosophy. In some cases, compensation committees will select a different peer group for their chief executive officer than other executives, and a different peer group for less senior employees. The rationale for this is simple. Executive searches for senior executives are national and in some cases international in focus. As you move down the organization chart the focus shifts from national to regional and for relatively junior management positions to a local basis.

It is advisable to review both peer groups on an annual basis in order to ensure continued relevance based on the company's current situation.

Developing a Pay Positioning Strategy

If superior levels of corporate goals are planned, it is necessary to position and target compensation levels accordingly. As with other parts of the compensation philosophy, the pay positioning strategy is set at the beginning of the year, and consists of the following:

- Percentile ranking of components of pay vs. market: For salary, bonus, long-term incentives, pension, health and wellness benefits, perquisites, and severance practices, a compensation philosophy should specify how each element of compensation is set. Most companies target the median (50th percentile) for setting total compensation, with variations for each element.

- Pay mix: This consists of salary, short-term incentive ("STI") compensation and long-term incentive ("LTI") compensation. Companies must consider the following factors when thinking about pay mix:

- Mix of salary, STI and LTI

- The STI/LTI ratio

- Performance measure comparisons between STI and LTI

- The LTI mix:

- Restricted stock

- Stock options

- Performance shares

- Pay for performance curve: This consists of threshold, target, and maximum payout. The threshold varies by relative or absolute, the target pays out at 100%, and the maximum is for 75th percentile performance.

Percentile ranking in comparison to the market is a very important concept in communicating a compensation philosophy as it allows management to translate the board's intention into practice. Base salary should be compared against the market on a percentile basis. For example, the 50th percentile is also referred to as the median. That is, 50% of the salaries of the peer group are above the salary of interest, and 50% of the salaries in the peer group are below the salary of interest.

The purpose of a pay strategy is to increase the company's profitability. You don't want to under-compensate employees as they will leave the company due to low pay, and you do not want to over compensate employees resulting in corporate waste. There is a relationship between turnover rate and competitive market positioning.

Salaries may exceed market median rates for those whose skills are superior to typical executives with similar responsibilities, or for those who hold positions that are uniquely important to the corporation. For certain key management positions in which the corporation must ensure the highest level of talent and performance, the corporation might target the 75th percentile. Conversely, salaries may lag median market rates for those who are new to a job or who hold positions of lesser importance.

To avoid increased fixed costs, extraordinary accomplishments or contributions should generally be recognized through annual incentive payouts, rather than through salary increases. Exceptions are acceptable for incumbents whose salary falls below targeted levels.

The LTI mix will have a significant effect on LTI payout depending on corporate performance. As an illustration, we show four possible LTI mixes in relation to various levels of corporate performance. These four LTI mixes are as follows:

- Mix 1 100% stock options

- Mix 2 100% restricted stock

- Mix 3 100% performance shares

- Mix 4 50% performance shares, 20% restricted stock and 30% stock options (this represents a "typical" large company LTI mix)

In our example below, Mix 1 fares well with superior corporate performance, but does poorly elsewhere. Most large companies use a blended/balanced approach of mixing stock options, restricted stock and performance shares (Mix 4). With this approach, the payout curve is flatter, but able to provide retention payouts even with poor corporate performance.